April 20th is designated as the UN Chinese Language Day for the legend on how Chinese characters are invented. It was chosen as the date to pay tribute to mythological figure Cang Jie 倉頡, who is associated with the creation of characters in some early texts. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) established a different day in 2010, but it has been celebrated on April 20 since 2011.

“Gu yu” (Rain of Millet) by Lin Dihuan 林帝浣

The myth of Cang Jie says that his noble endeavor was recorded to have caused “the deities and ghosts cried and the sky rained millet.” Gŭyŭ (rain of millet 谷雨) is the 6th of the 24 lunisolar terms in the traditional East Asian calendar, usually falls on days between 4/19-4/21. We are expecting a lot of rain and storm on the Chinese “rain of millet” day in Shenzhen this year. Cang Jie’s legend will continue to be remembered; the charm of the Chinese language and writing will be redefined and refined by his decedents.

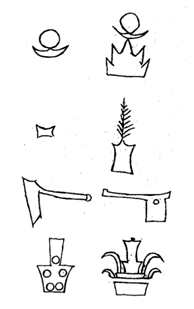

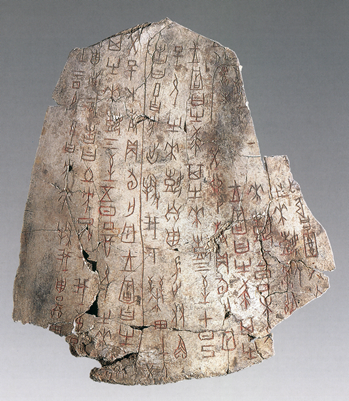

Dr. Yang at the Humanities Science Center at SUSTech started her research on Chinese writing system as an undergraduate student. Her B.A. thesis is an analysis of the “symbols on potteries in the Neolithic period.” Scholars have been divided on these ancient symbols. Some speculate that these inscriptions could be real words and the precursor to “oracle bone inscriptions” (jiăgŭwén 甲骨文). Oracle bone inscriptions are texts carved on the shells of turtle and shoulder bones of oxen for divination purpose by the late Shang people (c. 13th–11th cents. BCE).

Symbols on pottery from the Neolithic site of Da wen kou, Shandong. 4500-2500 B.C.E.

It is the earliest Chinese writing we have discovered up to now, and thus Shang is usually identified to be the start of Chinese history with reliable records. Dr. Yang researched some of these “shell and bone writings” from the ancient Zhou state, centered around what we now know as Shanxi Province, during her graduate studies in the School of Archaeology of Museology at Peking University.

The first time she had a chance to touch and hold a piece of the oral bones was at the library of the Chicago University when she was attending a workshop on archaic writing at the Creel Center there in 2009. Dr. Yang studied textual criticism at the University of Washington (Seattle), where she was trained in linguistics, textual studies and art history.

Pursuing a doctoral degree and doing research in the United States provided her with an opportunity to reexamine her scholarly work on Chinese writing and her cultural heritage from an alternative perspective. She was fortunate to work with scholars in different fields including curators at Seattle Asian Art Museum, where she worked as a research intern (2005) and participated in the exhibit projects on writing, Shu: Reinventing Books in Contemporary China and Fragrance of the past: Chinese calligraphy and painting by Ch’ung-ho Chang Frankel (張充和) and friends.

Although the Chinese language is becoming increasingly popular among second language learners all over the world today, there has always been a mysterious aura about it, whether it is the tonal nature of the language, the “monosyllabic myth,” or perhaps the antiquity of its non-romanized script. Some people have stayed away from the Chinese language when studying a second language because of those features while others have chosen to study Chinese for those exact reasons.

This still ongoing debate between fascination and idealization on Chinese can actually be traced back to the 13th century when some firsthand records about Chinese language and writing reached Europe. In the 17th century, the interest in Chinese culminated with serious discussions among European intellectuals with the possible identification of Chinese as a candidate for the “universal language.”

The seventeenth-century European search for a lingua universalis arose from the biblical belief that a clear, simple language given by God to Adam was lost after the dispersion of Babel. It was a language all living things were able to understand. Ever since this hypothetical common tongue was lost, different languages developed, which led to mutual unintelligibility among people. Investigations into a universal language scheme in the 17th century were fueled by new information that had been collected from 16th-century voyages and reports from overseas Jesuit missions.

Francis Bacon (1561–1625) proposed the concept of the universal intelligibility of Chinese in The Advancement of Learning (1605): “It is the use of China […] to write characters real, which express neither letter nor words in gross, but things or notions.” Bacon’s observations greatly stimulated his contemporaneous colleagues to look into the Chinese language and writing as a model universal language.

Viewing Chinese as the universal language “to the Whole world before the Flood” (John Webb, 1699) was just one of the many phases of Western approaches to the Chinese language. Since the late 17th-century, the study of Chinese language continued to progress and become increasingly comprehensive and sophisticated in Europe.

In China, the most radical revaluation of the Chinese writing system was probably the attempt to romanize Chinese script since the late 19th century. When intellectuals took a critical stance towards the character-based writing system, some believed that romanization of the characters and a new designed alphabet order would promote the modernization of China. It was thought such an approach would efficiently reduce the national illiteracy rate while fostering science and technology. Some left-wing intellectuals even advocated the abolishment of Chinese characters altogether (e.g., Lŭ Xùn 魯迅). Naturally, this proposal did not come to pass, and characters remain the standard script of China today. However, the romanization movement of the 1920s and 1930s led to several Chinese transcription schemes. The efforts in the 1920s and 1930s ultimately paved the way for the later installation of Hànyŭ pīnyīn 漢語拼音 in 1958.

In the long history of the cultural exchanges between China and the West, Jesuit missionaries, merchants, intellectuals, reformers, officials, students have all taken part in shaping our ever-changing understanding of the Chinese language and the culture and tradition in which it is deeply rooted.

Now, as a lecturer teaching Chinese academic writing for SUSTech for almost a year, Dr. Yang felt that she actually has learned a lot about her mother tongue from her students – the vibrant, catching, humorous language style of her young students. There is both boldness and subtlety with nuanced sighs and aspirations in how young people assure and convey themselves. Working on her ancient scripts research, while advising and working with her students every day provides a lot for her to reflect on the language and culture and how they interact with each other.

Recommended further reading:

Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics

Proofread ByChris Edwards

Photo ByCenter for Humanities, Qiu Yan