Recently, a research group led by Associate Professor Ming-Yuan SU from the Department of Biochemistry and the Homeostatic Medicine Institute at Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) published their findings in Nature Communications. Using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), the team resolved the dynamic structure of the human COP1-DET1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Their findings revealed the molecular mechanism by which substrates induce the E3 complex to transition from an inactive stacked assembly state to an active state, providing key insights for studying ubiquitin-mediated regulation and related diseases.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as a central pathway for intracellular protein quality control and homeostasis maintenance. By degrading short-lived regulatory proteins or misfolded proteins, it regulates critical biological processes such as the cell cycle and stress responses. COP1 (Constitutive Photomorphogenic 1), an E3 ubiquitin ligase first identified in Arabidopsis, mediates a highly conserved ubiquitination-degradation mechanism across both plants and animals. In human cells, COP1 forms the CRL4DET1-COP1 complex with DET1, participating in the regulation of cell proliferation and tumorigenesis by degrading transcription factors such as c-Jun and ETS2. Although the physiological functions of this complex are well-established, its assembly mechanism and the structural basis for its activity regulation have long remained unresolved.

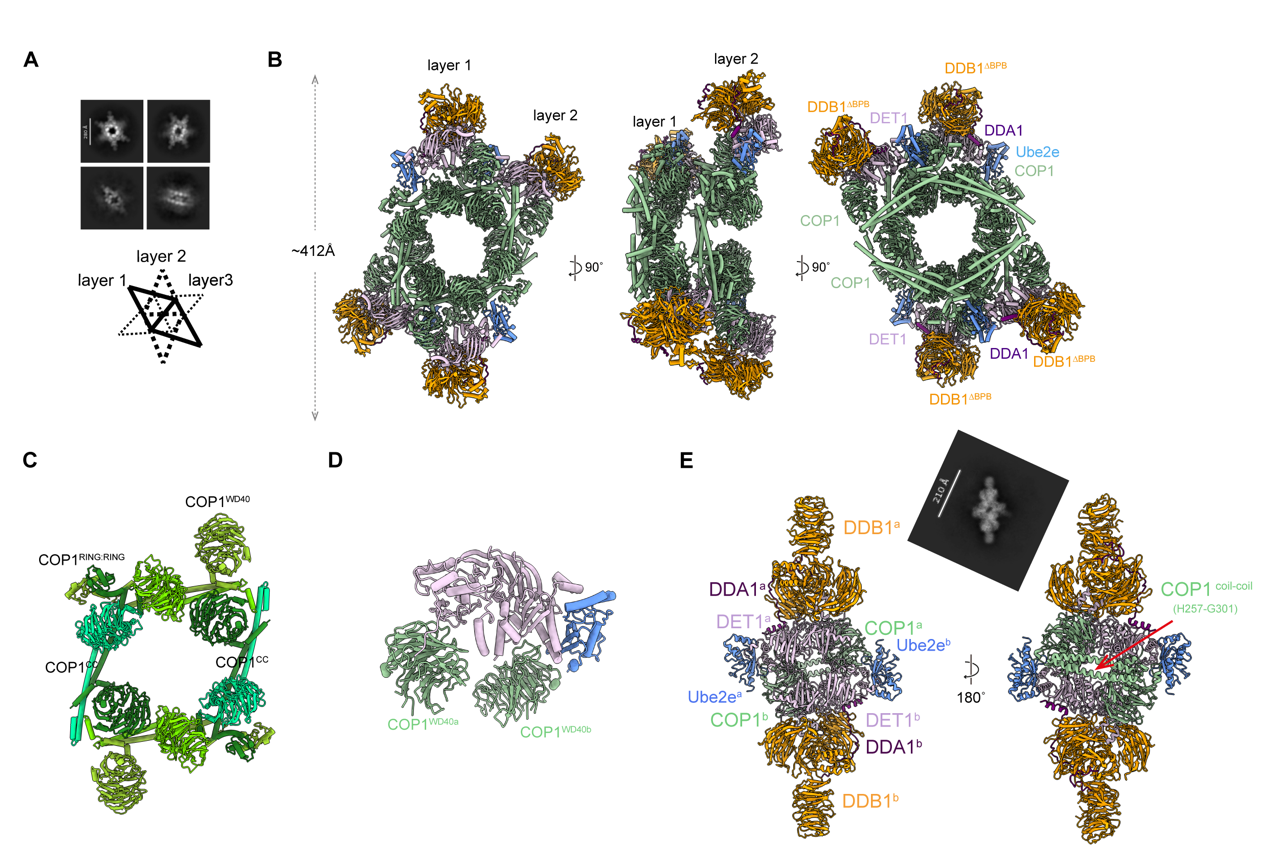

The team elucidated the dynamic conformations and functional mechanisms of the COP1-DET1 complex through integrated approaches, including cryo-electron microscopy, in vitro biochemical experiments, and structural modeling. Cryo-EM structural analysis revealed that the COP1-DET1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex adopts an ordered multilayer stacked structure in its inactive state. Viewed from above, it resembles a “hexagonal dart,” with adjacent layers rotated approximately 50–70° relative to each other (Figure 1A). Each layer comprises symmetrical subunits approximately 412 Å in length, containing eight COP1 molecules and two DDD-E2 (DDB1-DDA1-DET1-Ube2e2) subcomplexes (Figure 1B). The eight COP1 subunits intertwine via their coiled-coil domains, with DET1 serving as a structural scaffold connecting COP1 to both DDD and Ube2e (Figure 1C-D). Within each layer, the WD40 domains of COP1 molecules are oriented upward, while their coiled-coil domains are positioned downward, stacking sequentially atop the WD40 domains of COP1 molecules in adjacent layers (Figure 1B). This unique arrangement facilitates the formation of a stacked structure, shielding the substrate-binding site, the WD40 domain, and thereby inhibiting ubiquitylation activity.

Figure 1. Substrate-mediated assembly conversion of the COP1-DET1 E3 ligase complex.

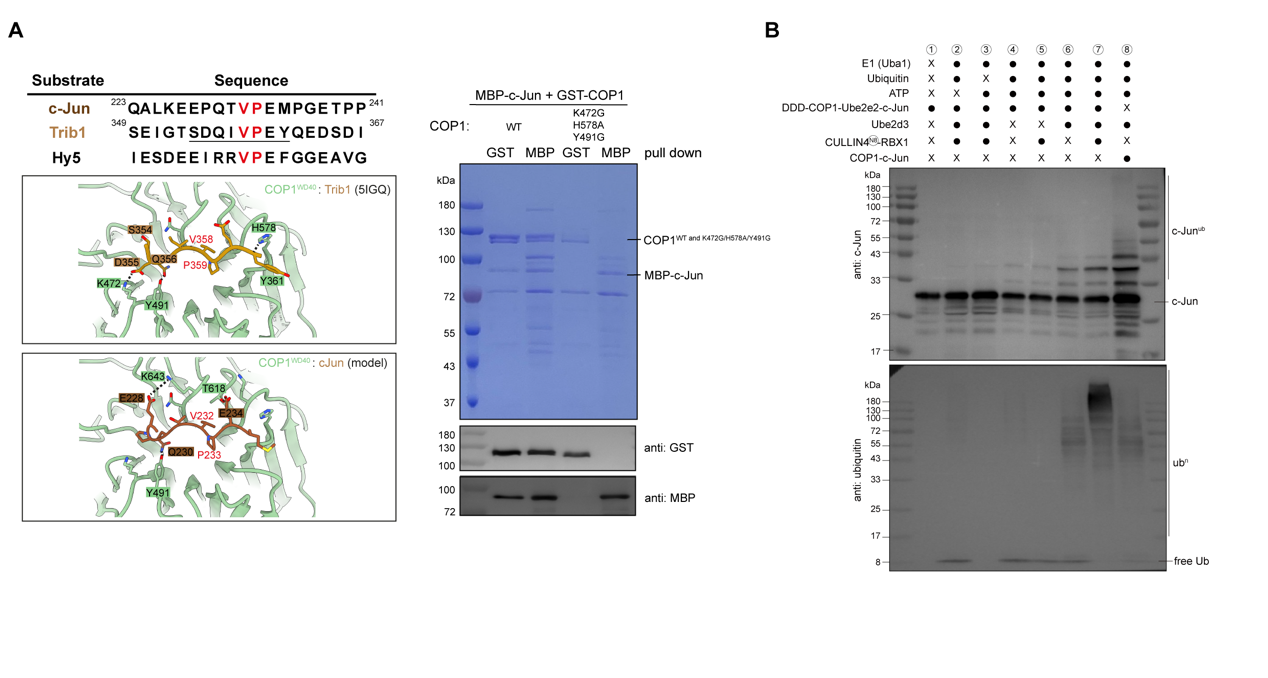

The team further discovered, through substrate co-expression and structural analysis, that COP1 substrates (such as c-Jun or ETS2) can induce the complex to transition from an inactive stacked state to an active dimeric state. Substrate binding disrupts the multi-layered stacked structure of the COP1-DDD-E2 complex, triggering COP1 to form a rhombic dimer (approximately 265 Å in length) via its coiled-coil domain, thereby exposing the substrate-binding site at the top of the WD40 domain (Figure 1E). This transformation serves as a critical switch for complex activation, ensuring substrate access to the catalytic center. Sequence alignment and in vitro pull-down experiments validated that residues K472-H578-Y491 at the top of COP1’s WD40 domain are the core sites for recognizing the substrate VP motif. Mutating these residues completely blocks COP1 interaction with c-Jun (Figure 2A). In in vitro ubiquitination experiments, the team observed a two-step reaction mode. DET1 acts as a scaffold protein, first recruiting the E2 enzyme Ube2e2 to complete the initial ubiquitination modification of the substrate. Subsequently, DDB1 binds to the CULLIN4-RBX1 complex, further recruiting the E2 enzyme Ube2d3 to achieve efficient extension of the ubiquitin chain (Figure 2B). This mechanism ensures precise labeling of substrates and their subsequent degradation by the proteasome.

Figure 2. Interaction sites of COP1 with its substrate c-Jun, and in vitro ubiquitination assay

These findings reveal the regulatory mechanism by which the CRL4DET1-COP1 complex responds to substrate signals through dynamic conformational changes, providing a novel perspective for understanding the activity regulation and ubiquitination specificity of E3 ligases.

Dr. Ming-Yuan SU from the School of Medicine served as the corresponding author, with Ph.D. student Shan WANG as the first author. Graduate students Fei TENG and Shuyun TIAN provided substantial support for the research. The study benefited from collaborative contributions by Dr. Goran Stjepanovic from The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Dr. Feng RAO from the School of Life Sciences.

Paper Link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-026-68375-7

Proofread ByNoah Crockett, Junxi KE

Photo ByYan QIU